As any regular readers will be aware, the GDPR is an act of the European Parliament which came into force in May 2018. It is designed to give individuals (formally called data subjects) far-reaching control over their personal data with severe penalties for any bodies (formally called data controllers) who cause a data breach that fails to protect that data or act in accordance with the existing agreement with the individual.

Two of the key tenets of the act are the right of access and the right of erasure:

A Data Subject Access Request could be summarised as allowing the individual to ask a data controller what personal information it, and it’s sub-processors, holds about them and to request a copy of this data in addition to being transparent about how this data is processed on their behalf. Typically this takes the form of an email or online form that the individual will complete with their name and minimally identifying information which is sent to the controller who responds with the full data set in the most human-readable form possible within 30 days.

The Right to Erasure, also known as the right to be forgotten, is similarly summarised as allowing individuals to make a request instructing that the information previously provided be deleted in whole or in part, which the controller must comply with by erasing or pseudo-anonymising this data in such a way that it can no longer be linked to the individual.

So how could this cause a data breach?

GDPR is certainly well-meaning and as is so often the case the issue arises in the implementation of these powers by Data Controllers.

In short, attackers have discovered that many companies, in their role as Data Controller, do not validate who made the request before providing or erasing the data.

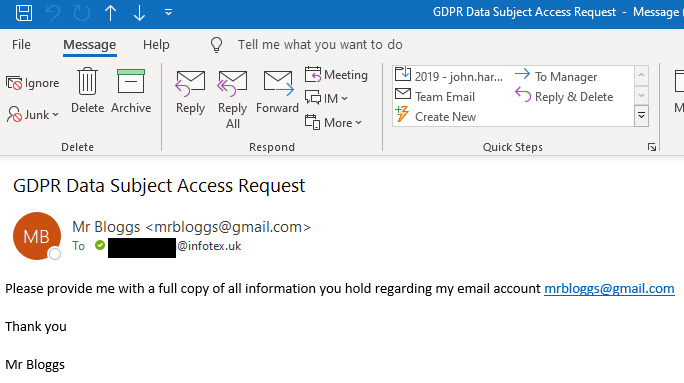

Let’s take a simple example, our attacker is looking for information to conduct an identity fraud against Mr Bloggs, they contact Company A who receives an email looking like the below:

Stop for a moment and imagine you received this request with your email address in the To: field. Would you process the request and reply to Mr Bloggs with the requested information?

Are you quite sure??

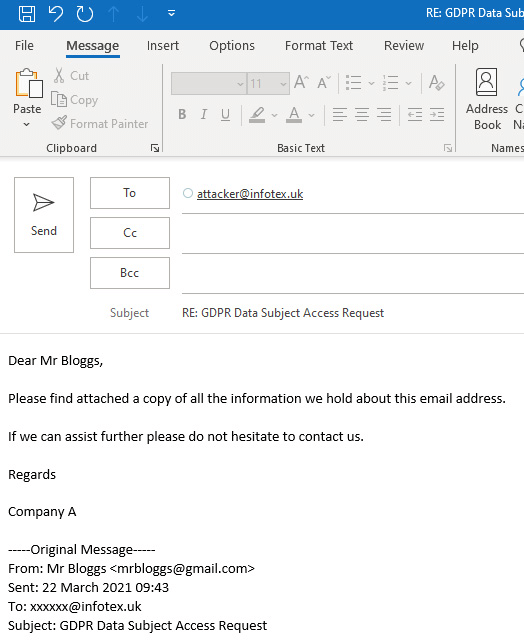

Look carefully at the below screenshot of where your reply would actually be sent to:

The trick here is that the attacker utilised a long-established email header called Reply-to causing the original email to appear to be faked to originate from mrbloggs@gmail.com while the response would be sent back to an entirely different address, attacker@infotex.uk in this example.

If the above response was sent with an attachment containing all the personal information held about Mr Bloggs, then that personal data would now be in the hands of the attacker helping them to conduct whatever identity fraud they had in mind.

By the simple act of sharing this information without Mr Bloggs explicit consent Company A have just unwittingly caused a data breach, for which they could be prosecuted under the very GDPR that they thought they were complying with.

How could this apply to a Right of Erasure request?

In the case of Right of Erasure requests, in many cases companies who receive such requests simply permanently delete, or anonymise, the customers data and reply confirming that this has been erased. This can be even worse as there is no need to send a reply-to header, simply fake the email address which the request came from and you have just deleted Mr Bloggs data, the first he knows is when he next contacts Company A and finds that they no longer know anything about him, potentially losing any files, order history, product warranties etc held by them on his behalf.

In this instance if requests are blindly processed then even without a reply-to header the data has been destroyed before the actual individual knows anything about it, perhaps the attacker may add a CC so that the company can let them know that the data has been deleted as well!

How can I protect myself as a Data Controller?

The first thing is to ensure that you scrutinise any requests received, in particular ensuring that the email address you are replying to is the account you hold on record.

As the act allows up to 30 days to comply with such a request you may also wish to send an email or call Mr Bloggs (ensuring not to reply-to the original email) to confirm & validate the request, this may also give customer service benefits allowing any grievance that has led to a legitimate request to be dealt with more amicably while also allowing a legitimate customer to respond and query the request.

If you have automated systems to process requests, test how they handle reply-to and CC email headers to ensure that they are not allowing data to be handled in unintended ways.

Credit to Hx01 (https://twitter.com/hxzeroone) whose paper inspired this post.